Peter Everington (September 25, 1934 – May 14, 2025)

A Tribute by Philip Boobbyer at the funeral, St Dunstan’s church, East Acton, June 6, 2025)

John (Peter’s son) has asked me as a friend of the family to say some words about Peter’s life, work and faith.

Peter grew up north of London, in Hertfordshire. His father was a lawyer, his mother a homemaker. The Second World War loomed large in his childhood; he and his brother Roland were evacuated to Norfolk during the Blitz. At school he showed promise academically, and he got a place at Cambridge to do Classics. Prior to that, he did military service in Hong Kong. He then took a job as an assistant teacher in Northern Ireland. Here he had a life-changing experience. Peter’s mother had taught him the Lord’s Prayer in an air raid shelter during the war, and in his teens he wanted to be a church minister. But a teacher colleague, Lloyd Mullen, challenged him to go deeper in his faith, through the practice of prayerfully listening to God, and doing a moral inventory of his life. Something stirred in him, and he gained new insights into his own character. Through this, he said later, he stumbled into a new dimension of God’s grace.

Lloyd was involved in a faith-based movement called Moral Re-Armament (MRA), now known as Initiatives of Change, and this episode marked the beginning of Peter’s lifelong involvement with this work.

This was in Spring 1955. Another turning point in Peter’s life took place the following year when he was starting his second year at Cambridge. This was during the Suez crisis. Peter was dismayed by Britain’s involvement in the invasion of Egypt in October 1956, and the deceit that went with it. As he was trying to make sense of his feelings, he sensed God saying to him that he wanted a bridge built between Britain. Egypt and the Arab countries, and that he (Peter) could have a part in this by using his language skills to study Arabic and being ready to go to places in the world where British people might be needed to serve.

As a consequence, Peter switched his degree course to Arabic for his final year, to the puzzlement of his parents, and then left Cambridge in summer 1958 not to be a vicar but to take up a teaching job in newly independent Sudan. His first job was in the city of Port Sudan, at the only government secondary school in a region roughly the size of France. Jobs followed at Khartoum Secondary School and a Teaching Institute in Omdurman. He was in Sudan for eight years and then returned on visits 25 times thereafter. He loved the country and was awestruck by its grandeur and beauty.

Peter’s memoir of his Sudan years was entitled Watch Your Step Khawaja—Khawaja meaning ‘white man’. These were words spoken to him during the Sudanese intifada of 1964, and in using this phrase Peter was effectively saying that the British needed to act with sensitivity in their former colonies, and that he had had to learn this himself.

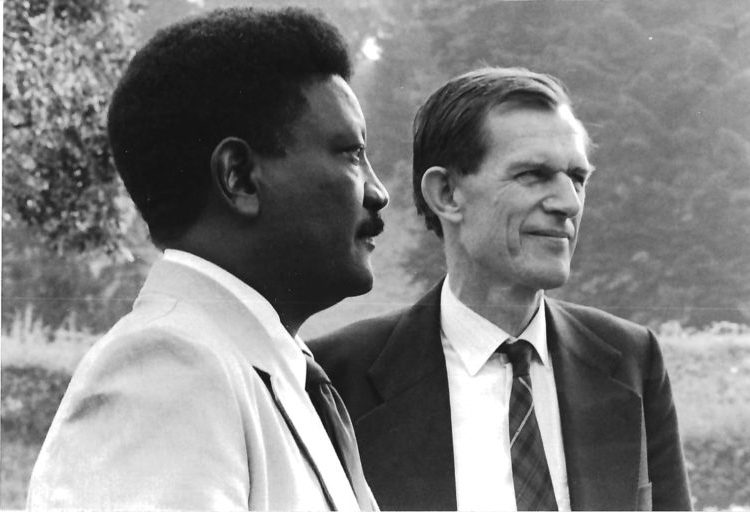

Sudan was riven with tensions between the Muslim north and the Christian south. In conflict situations, MRA focussed its efforts on trying to heal underlying hatreds. Peter was involved in this kind of work in Sudan. He saw his part as one of supporting key players. One of them was a Muslim from the North, Mohammed El Murtada Mustafa, who later headed Sudan’s Ministry of Labour, and who became a lifelong friend; another was the southern Christian leader, Buth Diu, who had found freedom from his hatred of the North. Inspired by the mantra, ‘It is not who is right but what is right’, they worked together, and some of their ideas fed into the national peace agreement of 1972. One of the signatories of that agreement was General Joseph Lagu, a guerilla leader who later became Vice-President of Sudan before going into exile in London. Peter and Lagu worked closely together for roughly 17 years from the mid-1980s onwards. Some of Lagu’s family are here today.

Peter was respected in Sudanese circles. In 1996, when two of his former students from Khartoum Secondary were President and Vice President, he was awarded the prestigious Order of the Two Niles for his services to Sudan. He was, of course, very distressed by the civil war currently raging in the country.

Returning to the UK in 1966, Peter did a year at Reading University before deciding to work full-time with MRA. Here some of his time was devoted to a student exchange programme run by the British-Arab Universities Association. Another venture was going to live in Iran—Peter and Jean lived there for two and a half years after they were married in 1972, at a time when the Shah was still in power.

On one occasion, on Iranian tv, Peter and Jean recounted a story of how they tried to solve domestic disputes. During a visit to India after they were married, the two of them had had a tense stand-off over what Peter saw as Jean’s impulsive driving. In a time of quiet reflection about this, Peter had the thought that Jean was a better driver than he was, and Jean shared that she needed to be more caring of her passengers. After some honest conversation, harmony was restored. The story struck a chord with the Iranian audience. The tv presenter said that he, too, sometimes had arguments with his wife about driving; and people in the street then approached Peter and Jean to ask if they were the couple concerned!

Peter wanted to see better relations between Christians and Muslims. He thought it possible to find common ground between the faiths, while not glossing over real differences. What he meant is illustrated by an episode from his years in Sudan when he reacted angrily on discovering that a dental appointment he had planned had been cancelled without warning, only to notice that a Muslim patient reacted much more graciously than he did. From such occasions, Peter concluded that at the level of human nature, people of different faiths were very similar. ‘Haste is from the Devil. Patient waiting is from the Merciful’ was a verse he liked in the Koran.

Peter was passionate about encouraging people. It was a regular thing for him to spend two hours, or even two days, working on a letter to someone, offering care and creative thought on how they could best contribute to the world, in the light of their experience and gifts. There was sometimes a challenge in what he said too—he was not a people pleaser. He believed that deep changes of heart and perspective, of the kind he had experienced in his earlier years, were possible for anyone. He valued encouragement himself: behind what to some might have appeared an austere manner, he at times wrestled with self-doubt.

For over thirty years, Peter was a kind of mentor to me. During the last three years, following the invasion of Ukraine, he and I, and a small group of friends from Russia, France and Germany, would meet weekly to have times of silence together, and then share reflections about our lives and what was going on in the world. A quote he loved was the line from St Peter’s first Epistle, ‘Humble yourselves under the mighty hand of God’.

A tall man, Peter walked with a long stride. After university, he walked out into a world grappling with the end of empire. As a friend, he walked alongside people in all sorts of situations, some of them here today. To the end, he was full of life and curiosity; to use a cricketing analogy, he was like a batsman who stayed at the crease right up to close of play, hitting the ball all over the park. Then, suddenly, he walked from the field and was gone. He was a bright light in our world, and we will miss him.