The last time Gulwali Passarlay saw his mother, she said: ‘Be safe, Gulwali. No matter how bad it gets, don’t ever come back’. As she sent Gulwali and his brother, Hazrat, off on the long journey from Afghanistan to Europe she urged them to ‘hold on to each other and stay together’.

A new edition of The Lightless Sky has been published by Atlantic Books, ISBN 9780062443892

Smugglers separated them the next day. Aged 12, Gulwali travelled alone, for over a year, through nine countries, not knowing if the next day might be his last, if he would ever find refuge or be reunited with Hazrat. He eventually reached the UK ‘trapped inside a sealed refrigerator lorry with bananas’. Gulwali tells the story of his terrifying journey in his book, The Lightless Sky, published in 2015. It has been translated into seven languages and distributed in eight countries, with a film in the making. It led to the creation of My Bright Kite, a grassroots Community Interest Company (CIC), which advocates for the wellbeing and inclusion of young refugees living in the UK.

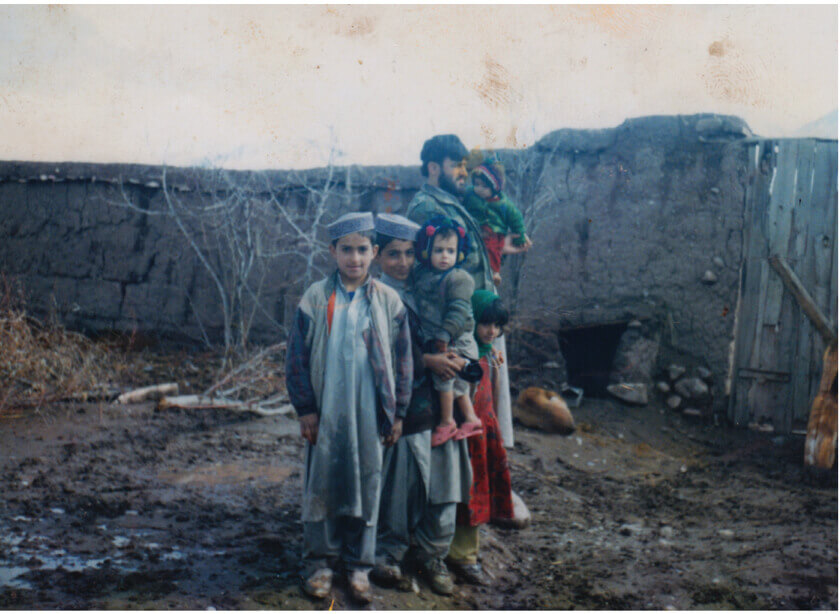

Gulwali grew up in a conservative Pashtun family in eastern Afghanistan. He recalls helping his grandfather tend the sheep and at night falling asleep under a vast, star-filled mountain sky. His father was a doctor, the first man in the family to receive a higher education. Such was his standing that Gulwali and Hazrat were known as ‘the sons of the doctor’.

His father, grandfather and so many relatives are now dead – killed by US forces. ‘Every type of bomb except nuclear bombs rained down on my country,’ he says. Children are born with diseases and deformities caused by their toxic effects: two out of five die before their fifth birthdays.

The Taliban wanted the two boys to become fighters or even suicide bombers to avenge their father’s death. ‘Revenge is a central yet often lethal part of the Pashtunwali code,’ Gulwali says. ‘If you don’t avenge yourself against your enemies, you have failed as a man.’ In 2006 his mother, with her deep faith in Islam’s prohibition of the taking of life, arranged for her sons to ‘be sent away’.

In The Lightless Sky, Gulwali describes the ‘unspeakable indignities and dangers’ of his journey. He travelled more than 12,000 miles, trekking over treacherous mountains, suffering imprisonment and cruelty in Turkey and Bulgaria, jumping from a speeding train. He had bullets fired at him by border guards. ‘There was rarely a day when I didn’t witness man’s inhumanity to man,’ he says. ‘Any childhood innocence left me.’ Many times he considered giving up and returning home. The only reasons he kept going were the memory of his mother’s face and the encouraging news that Hazrat had made it to England.

Gulwali was 13 when he arrived in the UK, after a month in the infamous Jungle in Calais. ‘I just knew I couldn’t spend another night in the cold, wet filthy conditions of the camp, where rats and cockroaches ran over our heads as we tried to sleep on beds of cardboard,’ he writes. He arrived in England without documents. UK immigration officials did not believe he was a child and interrogated him for four hours, through a Pashtun translator. They finally concluded that he was ‘too smart’ to be 13.

‘The authorities wouldn’t believe my age, my nationality, or anything I told them,’ he says. He was issued with new documentation that stated he was 16 years old, denying him the rights due to an unaccompanied asylum-seeking child. ‘There is nothing worse in life than not being believed,’ he says. He was threatened with deportation twice and felt that he had been lost in the system. Things got so bad that he wanted to kill himself.

He says that he was ‘emboldened’ to tell his story for those who did not make it. ‘Giving them a voice is ultimately why I wanted to write my book,’ he says. His dream is that ‘no child has to wake up to another lightless sky’ and that the day will come when a child reads his book and asks, ‘What was a refugee?’

According to UNHCR, over 70 million people around the world have been forced from their homes. Among them are nearly 25.9 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18. ‘I hope by telling my story I can help people from both sides of the debate understand and come together,’ Gulwali says. He is distressed about the number of young refugees that the UK has sent back to conflict areas once they reached the age of 18 – nearly 3,000 between 2007 and 2015.

My Bright Kite

Among the many people who were moved and inspired by Gulwali’s book was Nola Ellen, who had been running a project for children in the Jungle. ‘Some books touch your heart and leave an imprint forever,’ she wrote. ‘Your story has the ability to inform and inspire those who work frontline with refugee children.’ After corresponding, they finally met and, in October 2017, they co-founded My Bright Kite.

Gulwali and Nola work to raise awareness by delivering workshops and talks on the personal lived experience of a refugee. They deliver tailored storytelling workshops for unaccompanied minors dealing with child trauma and also connect refugee children in the UK and overseas with schoolchildren in the UK.

Gulwali’s own experience is a testament to the contribution that refugees can make to society, if given the right support and help with integration. He says that ‘his second chance at life began’ when, three years after his arrival, the authorities recognized him as a child and placed him in foster care. He started school, learnt English, developed his skills and integrated into the community. In particular, he mentions his headteacher at Starting Point in Bolton, Mrs Kellet, who restored his faith in kindness and humanity. ‘She listened to me, smiled and said: “Gulwali, I believe you.” Although the system did not value me these people did.’ Teachers, foster carers, and youth workers encouraged and urged him on. He went on to study at the Essa Academy, where he exceeded all expectations by getting 10 GCSEs, all above C grade, and won many certificates of achievement for contributing to school life. In 2015 the school set up an annual award in his name, for overcoming adversity.

In 2012, he was selected to be a torchbearer for the London Olympics. He says that, of all the many national awards he has won, this was one of his proudest moments.

Manchester University, where he gained his degree in Politics, made him Student of the Year in 2016. Earlier this year, he completed a Master’s in Global Diversity Governance at Coventry University. As he stepped up to receive his degree he thought of how proud his mother and father would have been at his achievement and how sad he was that they could not be with him to witness it. He manages to talk to his mother once a week. He was reunited with his brother, Hazrat, not long after reaching the UK and now lives with him in Manchester.

‘We all have the power to help those around us or to harm them,’ he says. ‘The choices we make define our walk, define our own personal journeys and make us the people we are.’ His ambition is to ‘begin a slow reverse journey back home’: to return, ‘if it becomes safe enough for me’, to help to rebuild Afghanistan.