By Kenneth Noble

Kenneth Noble

The following piece is by Ken Noble, who has worked and volunteered with MRA/Initiatives of Change in various capacities for 50 years. Here he shares his memories of how he started volunteering, his early days in Malta, and what this experience taught him…

I finished my university exams in early June, 1971 and the next day started working as a volunteer at 45 Berkeley Square in Mayfair, which was a large residential home then owned by Moral Re-Armament (MRA). I found myself a part of the Travel Team which was that summer organizing seven charter flights to Geneva to help British people take part in the Caux conferences at the Swiss centre for MRA near Lake Geneva.

At some point during the summer I decided to volunteer with MRA on a long-term basis. No one seemed to object. There was no talk of a contract, payment, pension although the Secretary, Roly Wilson, had said something about expecting to travel a lot!

Shortly after that, I was invited to Malta to work alongside Peter Shambrook (now a main player in the Balfour Project), who had been part of Anything to Declare?, an MRA musical show that had traveled the globe. People in Malta who had seen the show had asked that one or two people should stay on there to help build a team of younger people who would try to live out the ideas of MRA. Also there were Ian and Sheena Sciortino, full-time volunteers with MRA who owned a house in Sliema. Ian was British but had a Maltese father.

Archbishop Gonzi meeting the cast of an MRA production "Song of Asia" (1975)

Malta was overwhelmingly Catholic and I was intrigued to discover that Mass in Maltese involved worshiping ‘Alla’. (Maltese is a Semitic language, following the islands’ occupation by Arabs for over 200 years.)

Malta had been a strategic base during the Second World War – Churchill called it ‘the unsinkable aircraft carrier’ – and it had been the target of many air raids by the German/Italian axis. The Maltese people had been awarded the George Cross for their stalwart resistance. And there was element, particularly among the upper-class Maltese, who looked back to the British colonial days with nostalgia. The country was deeply divided between the conservative Nationalist Party who wanted to keep the British monarch as the head of state; and the pro-republican Labour Party of Dom Mintoff. Many of the more conservative Maltese whom we met regarded Mintoff as pretty much the devil incarnate!

Independence from Britain was not long past (1964). While I was there, Mintoff, who was the Prime Minister, was campaigning to end the defence agreement with Britain that the Nationalists had signed when they were negotiating Independence.

The British authorities were, I think, keen to demonstrate how much more vulnerable Malta would be without a British military presence. Whatever the reason, they made a big show of sending helicopters around the main harbour in the capital, Valletta, with military ‘assets’ dangling below. Things were pretty tense. There were anti-British demonstrations going on. One night in Valletta Peter and I saw a demonstration heading down the street towards us. Despite our suntans, we were still conspicuously British. We took refuge in a phone box, just in case!

Peter and I got to know many young people. We both enrolled on courses in the University of Malta, partly to have a rationale for getting a visa but also so that we could meet people. So I took Maltese history – which, for such a tiny country, was extraordinarily rich. Like many Mediterranean countries it has ‘benefited’ from wave after wave of occupation.

One of the people we knew quite well was ‘Sloopy’. He was a prominent Labour Party supporter. Everyone knew him as Sloopy, to the extent that I had forgotten his real name. I’ve since Googled ‘Sloopy Malta’ and found an obituary of Joe Bartalo in a Maltese newspaper. He apparently remained true to his socialist principles until the end.

The person whom we got to know best was a young doctor, ‘Ernesto’, from one of Malta’s leading families. Ernesto took us round everywhere and introduced us to many people. I think he was also responsible for providing us with a small flat in a down-market part of Sliema. It was the sort of place that would not have impressed the H & S inspectors, with green slime flourishing down one leaking wall. But we were young and enthusiastic and unfazed by such things.

On occasions, Ernesto prescribed the Black and White Book by Sydney Cook and Garth Lean (Blandford Press 1972) to patients where he thought it would help them.

Our only regular income was a £5 postal order that Doris Derbyshire, an elderly lady in Stockport (Peter’s home town), used to send once a month. But we could live pretty cheaply. You could buy a bowl of rice at the university canteen for 5d; and a loaf of freshly baked bread for 6d. Hobz biz-zeit was a popular local delicacy, an open sandwich with olive oil, and sometimes capers or other goodies. We also got invited out for meals from time to time.

The Sciortinos had a projector and Peter and I often used to show MRA films to their friends, or at various venues around the islands. I wasn’t too clever technically, and had one or two mishaps as I threaded the film wrongly!

One of the main English-language newspapers carried a regular column written by ‘John’. He was clearly young and I had a strong sense that I was meant to meet him. I found out his address, and was keen to go there. But there was also an event at a Catholic retreat centre, where a film was to be shown. Reluctantly, I agreed that I would go and project the film. This had an unexpected pay-off when I learned that John was at the retreat! We became close friends, and I still occasionally exchange messages with him. He interviewed me for his column. Later, he served in various Cabinet positions.

There is a lot more that I could say about 18 adventurous months in Malta, but I think it was a good training ground for me in the basic practices of Initiatives of Change – daily quiet times and caring for people, not least through the mistakes I made!

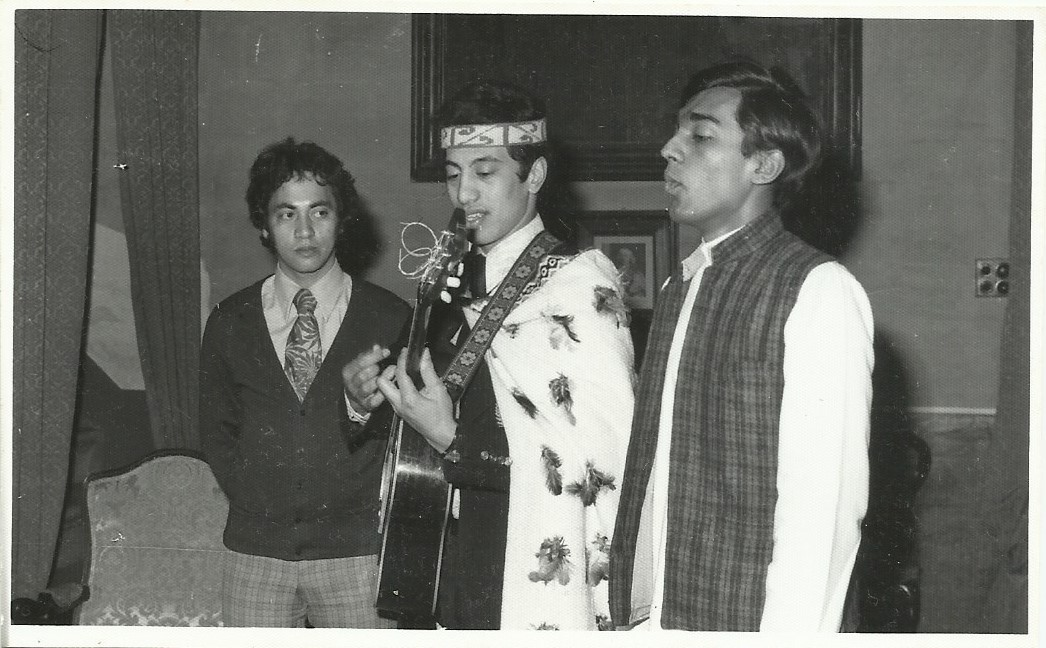

Some of the cast of "The Song of Asia" performing (1975)

What have I learned from those experiences in Malta?

Looking back, some 50 years later, I think that I was too ambitious to persuade people to live the way of life advocated by MRA, perhaps in order to prove something to myself or others.

I have no problem with the concept of helping others to find God’s plan for their life. But I think that there was a danger of trying to reduce it to a series of techniques. In my case, I think I engaged my head more than my heart. I am slowly learning that if we don’t love people, we easily start trying to use them. And of course people immediately recognize that.

I’m sure that people told me that ‘life changing’ has to be motivated by love, not ideological zeal, but the thought didn’t fully register. Perhaps I was so conscious of struggling to get the hang of absolute purity and honesty, that I gave little thought as to what was meant by ‘absolute love’. But clearly, at the very least, it involves wanting the best for other people and giving them reasons to trust you in your care for them. The Biblical injunction about dealing with the plank in your own eye before attempting to remove the speck from the other person’s eye is an important principle.

I also think I was guilty at times of trying to fit people into my plan rather than helping them to discover God’s plan for themselves. I was very inspired by the ‘cabinet of conscience’ model in Zimbabwe; and I had ambitions of bringing together some of the senior people we were in touch with, such as a leading priest, and a trade union leader, a very dedicated Christian, to form such a cabinet. But they couldn’t see the point!

Having said that, I do think that some of the Catholic leadership in Malta saw MRA as a way of strengthening the conviction and practice of professing Catholics – and perhaps of reaching some who were outside their flock. Certainly Archbishop Gonzi, the head of the church in Malta, and Mgr Victor Grech, the Rector of the main Seminary, visited Caux with a dozen seminarians in 1973 or 74. (Incidentally, Mgr Grech is now in his nineties. There is a picture of him greeting Pope Francis on the internet.1)

I end with some words of Mgr Grech which I found on the Foranewworld website. In 1979, he addressed nearly a thousand young people in Malta, representing many different youth organisations, who had organized a Festival of Peace. He said:

‘You are not seeking the peace of the grave, but the peace which is the fruit of change in man and society.

‘To make a good start on the road towards peace, I have to make a start with myself. For this I have first to put things right with God. Today’s man wants to change the world without wanting to change himself. Nobody can give away something he has not got. if I do not have peace in my own heart, I cannot give peace to others.’

Images of the cast of “Song of Asia” courtesy of John Azzopardi.

Header image of Valetta by Berit Watkin, his work is available to view here.