‘Parents are not in touch with the younger generation and families are growing apart,’ laments Samiya Lerew. She says that Somali-British suffer from a torn identity. First generation emigrants are scattered in ‘little bubbles of Somalia’ across the world, with their umbilical cord to home ruptured.

Samiya describes herself as ‘a product of colonisation’. Her grandfather was a politician, when Somalia and Eritrea were under Italian rule. Her mother was a Somali celebrity, a singer and broadcaster with Radio Mogadishu, and her father an Eritrean lawyer. ‘I am a beizani (a townie),’ she says. In her childhood, Mogadishu was a peaceful, multicultural, thriving hub. ‘It was an era of “modernity”, and women and girls had equal rights and relative freedom,’ she says nostalgically.

In 1982, Samiya came to the UK to study English and train in secretarial and administrative studies. But when her stepfather died, she was unable to continue her education. She felt obliged to find full-time work to support her widowed mother. She met her English husband while working for the Manpower Unit at the YMCA in Hornsey. She went on to work as a rate rebate officer at Haringey Council. Today, she lives in Barnet, north London. She values the fact that her two daughters, Simman and Elizabeth, and son, Edwin, are not just her children but also her ‘friends’.

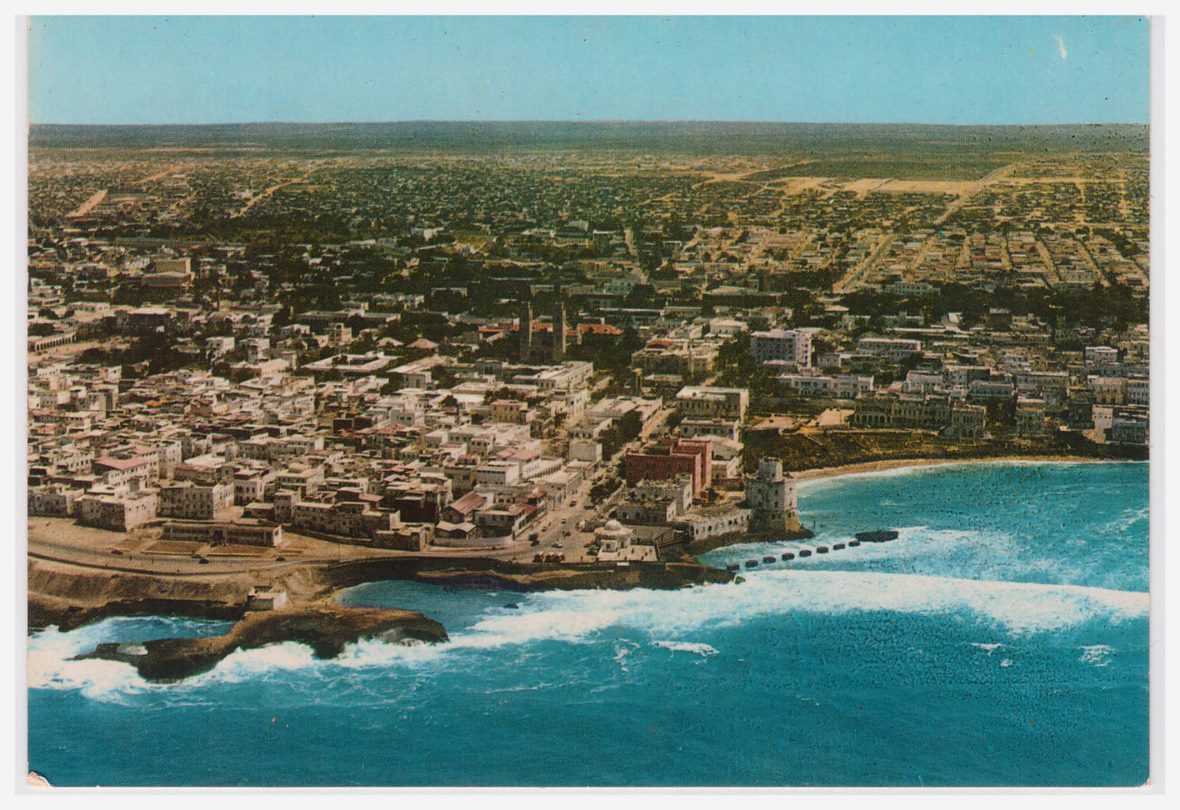

Mogadishu, Somalia, before the war

In 2014, Samiya applied to Birkbeck, University of London, to read Global Politics and International Relations. ‘I was delighted when I was accepted at the same university as Edwin,’ she says. The decision to study politics was partly to support her advocacy work for the Somali marginalised community. ‘I have always found it difficult to cut through the red tape unless I had “BA (Hons)” next to my name.’ She also saw it as a way of supporting Edwin with his education: she is convinced that gender inequality harms men as much as women. When mother and son graduated on the same day in 2017, the story was carried by the BBC.

British Somali parents in the UK are often unable to understand the challenges facing their children, or to assist them, she says. Edwin, now 25, was picked on at school because he was ‘different’. As Somali youth adopt relatively more liberal Western belief-systems, tensions intensify in their families. Mothers will often ‘enforce’ their sons to go to the mosque. Young people lose their way between divided worlds. Fear, ignorance and language barriers all widen the intergenerational gap. This is not just an issue for families and the community, Samiya maintains, but also one that the government needs to understand.

She believes that the key to political and social stability in Somalia is to break through tribal traditions. She explains that Somalis are made up of multiple clan groupings, whose relations play a central part in culture and politics. These clans are patrilineal and divided into many sub-clan divisions, which fight and discriminate against each other. She tells me the painful story of how her fiancé in Somalia broke off their engagement, because Samiya’s mother came from the wrong caste and clan.

Samiya, centre, with her family

Her advocacy work focuses on helping resolve conflict between the many marginalised groups in the rural areas of Somalia. She tells me about the extreme poverty and land grabbing, and its effect on people whose lives rarely extend beyond family, tribe and village. Somalia still lags behind other developing countries in defining frameworks that safeguard the interests of minorities, she comments.

We talk about the controversial custom of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), now a high-profile women’s rights issue. The demand for ‘circumcised wives’ is high, she explains, and mothers feel compelled put their daughters through this procedure. ‘Women circumcise their daughters out of love. It is the price they pay for their daughter to be marriageable.’

‘The education for boys is inadequate,’ she goes on. ‘They are unaware of the negative impact that FGM has on women and their society.’ Young men have been passively indoctrinated that brides are only desirable if they have been ‘stitched’.

The cycle will continue, she says, unless both young men and young women are educated on its cost. But she believes women are the ones to bring about change. When she got married she said: ‘No circumcision comes to my family.’ She adds, ‘I would not do to my daughters what was done to me’.’

Mother and son graduating in 2017

Photographers: Roger Way, Courtesy of Samiya Lerew