How did you become involved in the far-right movement?

At 14, I was a lost kid. I was looking for community, identity and purpose. I felt abandoned by my parents. One day when I was desperate, a man promised me paradise. He said, ‘Come with me and we’ll be your new family and I’ll give you a purpose.’ The group I joined, the Chicago Area Skinheads (CASH), was the first skinhead neo-Nazi group in the US.

If a soccer coach had come to me at the same time, I would have gone with the soccer coach – I love soccer. Nobody ever gave me the opportunity. I was smart, talented and ambitious, but I was shy and adults were busy. That’s where we’re failing young people. We need to find out what they’re passionate about, reinforce that and give them the chance to succeed in a positive way.

What did your family think of this ideology?

My family didn’t understand what I was involved in. Once they found out, I was so deep in, there was no going back, I wouldn’t listen. At 14 and 16, I wasn’t mature enough to understand the nuances of the politics, or even the racism, it was a social movement for me.

When I was 16, the man who recruited me went to prison. I stepped into the leadership void.

How did you recruit people?

We looked for kids who were marginalised, who were acting out and angry, who came from broken homes. We would listen for what was missing in their lives, promise and deliver it. To a certain degree, we did provide a family, an identity and a purpose. I eventually became the leader of CASH and then the Northern Hammerskins. At that point, I was in charge of about 500 skinheads.

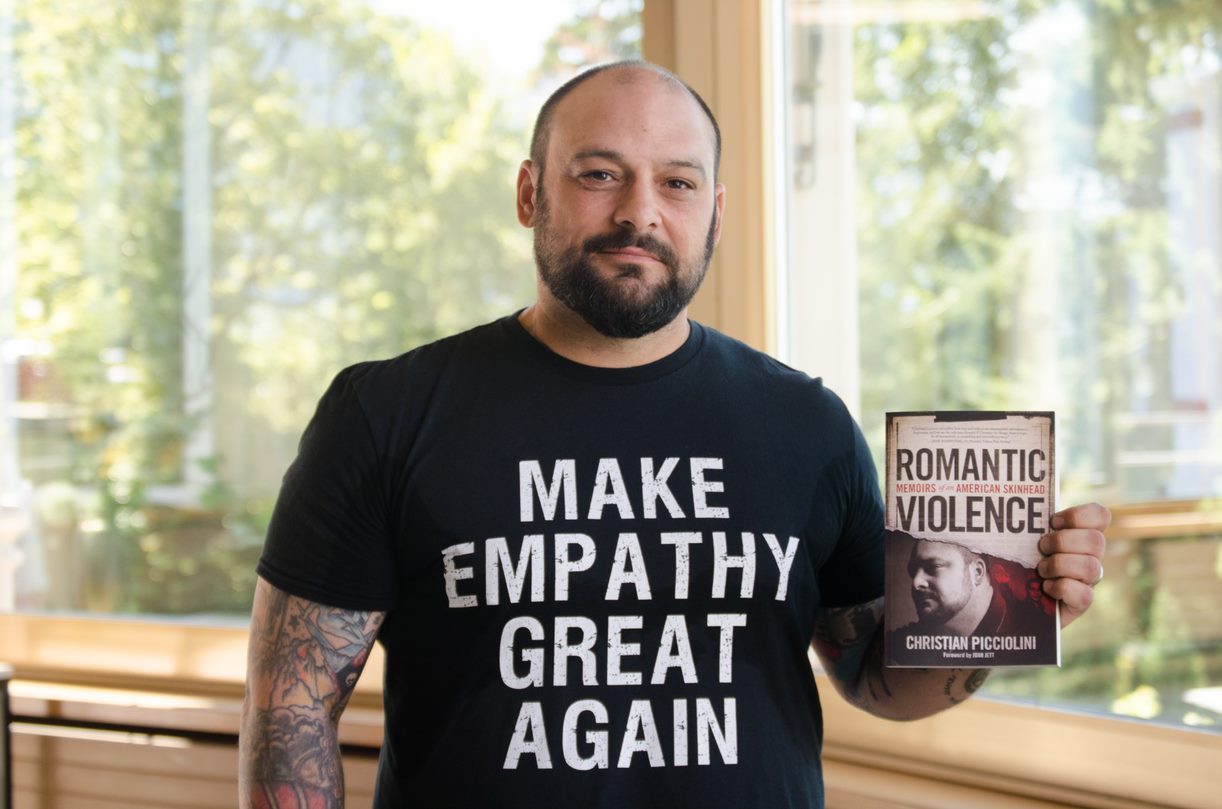

Christian with his book Romantic Violence: Memoirs of an American Skinhead

Was the group violent?

We were more focussed on marketing and music. Music was a propaganda tool. I started a band, because I knew it was a good way to indoctrinate young people. We’d clash violently with people who saw us the enemy – non-whites, but also whites who were opposed to us, the anti-racist gang, Antifa, and SHARP (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice).

What triggered you to leave?

I had doubts throughout, because I wasn’t raised to be racist: racism was something that I adopted just to belong. Ideology is not what radicalises people, but a broken search for identity, community and purpose.

When I was 18 I met a woman who was not a member of the movement and we married. We were married for four years, and had two boys. She pressured me to draw back. My compromise was that I would keep off the streets and open a store to sell white power music imported from Europe. No one else in America sold this music, and before I knew it, 75 per cent of my revenue came from it.

I also sold punk rock, hip-hop and heavy metal. This brought in people whom I wouldn’t normally have met. I had never had a meaningful interaction with anyone who wasn’t like me. I started to empathise with their situations like they empathised with mine. Ultimately, they got to me. They could have protested, they could have beaten me up, they could have broken my windows. But instead they showed me compassion.

Eventually my wife left me. By then, I was embarrassed at the kind of music I sold. It brought in so much of my revenue, that when I pulled it, I had to close my store. I lost my livelihood, wife and children. And even though I’d abandoned the movement, I was still branded a racist.

Five years after I closed the store, I went through a massive depression. Finally, in 1999, a friend told me to apply for a job at IBM, where she worked. I was tattooed, I was an ex-Nazi, I hadn’t been to college, I had been kicked out of six high schools and I didn’t own a computer. But I got the job.

On my first day they sent me to install computers at a high school I had twice been kicked out of. The second time was after I had had a fist fight with the black security guard, Mr Holmes. I was terrified someone would recognise me. Within the first five minutes Mr Holmes walked past me. I followed him and tapped him on the shoulder. All I could think to say was ‘I’m sorry’. He stuck out his hand. We embraced and he made me promise that I would tell my story.

I hadn’t told anyone, because I was scared of being judged. When I started to tell people, the burden lifted off of me.

Christian Picciolini, right, speaking at Just Governance for Human Security, part of the Caux Forum in Switzerland

Tell us about Life After Hate.

I co-founded Life after Hate in 2009, to tell our stories online. People wrote to us from all over the world, wanting to share their stories. They had thought they were the only ones who had gone through this. Life after Hate became a community which people could join, and so feel safe to leave the movements they were part of.

Now I’m starting a new global exit programme, which focuses not just on white supremacists but on all extremists. We want to be a beacon for people all over the world who are struggling. For instance, when I was in Slovakia, Bulgaria and Hungary, people said, ‘Nobody in our country has ever come out with their stories.’

What do we need to do to stop extremist groups?

These movements love violence against them. When protesters attack Nazis, it proves their rhetoric – that they’re being attacked and marginalised, that their freedom of speech is being suppressed. They use it as propaganda.

They love silence too. When we don’t speak out against them, it allows them to go unchallenged. The happy medium is to hold them accountable by a strong show of presence. A week after Charlottesville, two or three dozen neo-Nazis protested again in Boston, but 40,000 protesters surrounded them with candles. They said, ‘We’re here. We see you, but we’re not going to adopt your tactics. We just want you to know we’re here and we’re holding you accountable.’ That’s how you wage peace.

Charlottesville Candlelight Vigil at the White House, Washington, DC USA

What can ordinary citizens do when terrorist attacks happen and what can we do to reintegrate former extremists?

Support the victims. When somebody is hurting, we need to rally around them.

More Americans are killed by white supremacists than by any other foreign or domestic extremist group. Yet we don’t say that we have a white terrorism problem.

We need to provide more opportunities for people to leave that lifestyle. When you’re in, there’s no way out – either your group will hurt you or the police will arrest you. We need safe ways for people to leave. Otherwise they just push down their fears and confusion and act more extreme.

We shouldn’t look at them as monsters, but as broken people doing monstrous things. The more we call them monsters, the more it pushes them down their hole. We need to bring them closer, to embrace them. Every person I have worked with, myself included, has changed through the compassion of those from whom they least deserved it. People can change.